Taking up the challenge of the century, Hope Spots around the world – from Mauritius to the South African coastline – aim to focus on the dire need to keep our blue backyard clean and safe.

‘ONWARD AND DOWNWARD!’ For veteran marine biologist and oceanographer Dr Sylvia Earle, it’s a motto for life, having dedicated an epic career to underwater exploration and raising awareness around ocean conservation. At 88, she’s a living legend, the first TIME magazine Hero for the Planet, a National Geographic explorer-in-residence and founder of Mission Blue, SEAlliance and DOER Marine (Deep Ocean Exploration and Research). She has led over 100 expeditions, logged over 7 000 hours underwater, authored numerous books and lectured worldwide – and she’s not stopping any time soon. What motivates her to keep going? ‘Reasons for hope.’

Mission Blue now has 156 of them and counting – Hope Spots covering an estimated 57 577 967km² of the ocean, singled out by local champions passionate about protecting places critical to the health of Earth’s blue heart. These are notable for their abundance or diversity of species, a particular habitat or ecosystem, or having significant cultural or economic value to a community. Rolex supports the project as part of its Perpetual Planet initiative, which is focused on those who go above and beyond to protect and preserve the ocean. ‘Hope Spots are often areas that need new protection, but they can also be existing marine protected areas (MPAs) where more action is needed. They can be large, they can be small, but they all provide hope,’ says Earle.

The hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) is critically endangered. Marine turtles are protected under Mauritian law. This one is foraging on a broken bubble coral reef.

Spotting a weedy scorpionfish (Rhinopias frondosa) is tricky – with their fleshy tentacles and atypical shape, they disappear into the seaweed and algae. They’re commonly associated with the Coral Triangle but, based on her sightings, Greet Meulepas is convinced that this species is encountered more frequently in Mauritian waters.

Ask her why we should care about ocean conservation and she’ll quietly enquire if you like to breathe. As the so-called ‘lungs’ of the planet, the ocean generates most of our oxygen, acts as a carbon sink – limiting climate change by absorbing carbon dioxide – and hosts rich areas of biodiversity, often invisible to the naked eye. According to the United Nations, a ‘loose patchwork of weakly enforced rules governing international waters’ has enabled the exploitation of most of the planet’s oceans, whether through overfishing, acidification and pollution, or emerging threats such as deep-sea mining.

However, the United Nations High Seas Treaty, which was adopted on 19 June 2023, is another significant reason for hope. It’s a world-first legal framework that extends environmental protections to international waters and provides momentum to the drive to have 30 percent of our seas protected by 2030.

Meanwhile, on the small island of Mauritius (2 040 km² of land area), the location of one Mission Blue Hope Spot, the sea level rise measured in the capital of Port Louis is already almost one centimetre. This is according to Francois Gemenne, a researcher specialising in environmental and climate migration issues and climate change adaptation policies. The annual world average is significantly lower at 0,44mm. Beaches are getting smaller, and within those cerulean waters, coral reefs are dying, fish are disappearing, and cetaceans are running out of pristine habitats.

Reassuringly, sea temperatures have not risen above 29˚C. Mauritius resident Greet Meulepas, a biologist, marine and lacustrine scientist, cofounder of Beyond Scuba and awardwinning underwater photographer, is grimly aware of the human impact on this island her young family has called home since 2016. ‘Mauritius has the potential to be paradise on Earth: always balmy, tropical weather, beautiful mountains, temperate ocean, breathtaking nature, a rich culture, good-natured and creative people with a sense of humour and a talent for enjoying life – in short, an amazing place to raise a child,’she says.

But when she and her husband, award-winning videographer Olivier van den Broeck, both PADI-accredited divers, moved to the island, they noticed similar evidence of overfishing, pollution and climate change to what they had witnessed elsewhere. Runoff from agricultural activities (pesticides, herbicides and fertilisers) and construction works close to shore contribute to the decline of the coral reefs. In addition, grazers like parrotfish, which live off the algae on the reefs, are being caught. The resulting uninhibited algae growth causes the corals to suffocate. Meanwhile, big trawlers and longliners are scooping the oceans empty, and local fishermen who use simple fishing lines have no choice but to resort to fishing in lagoons where juveniles live with little chance of being able to reproduce.

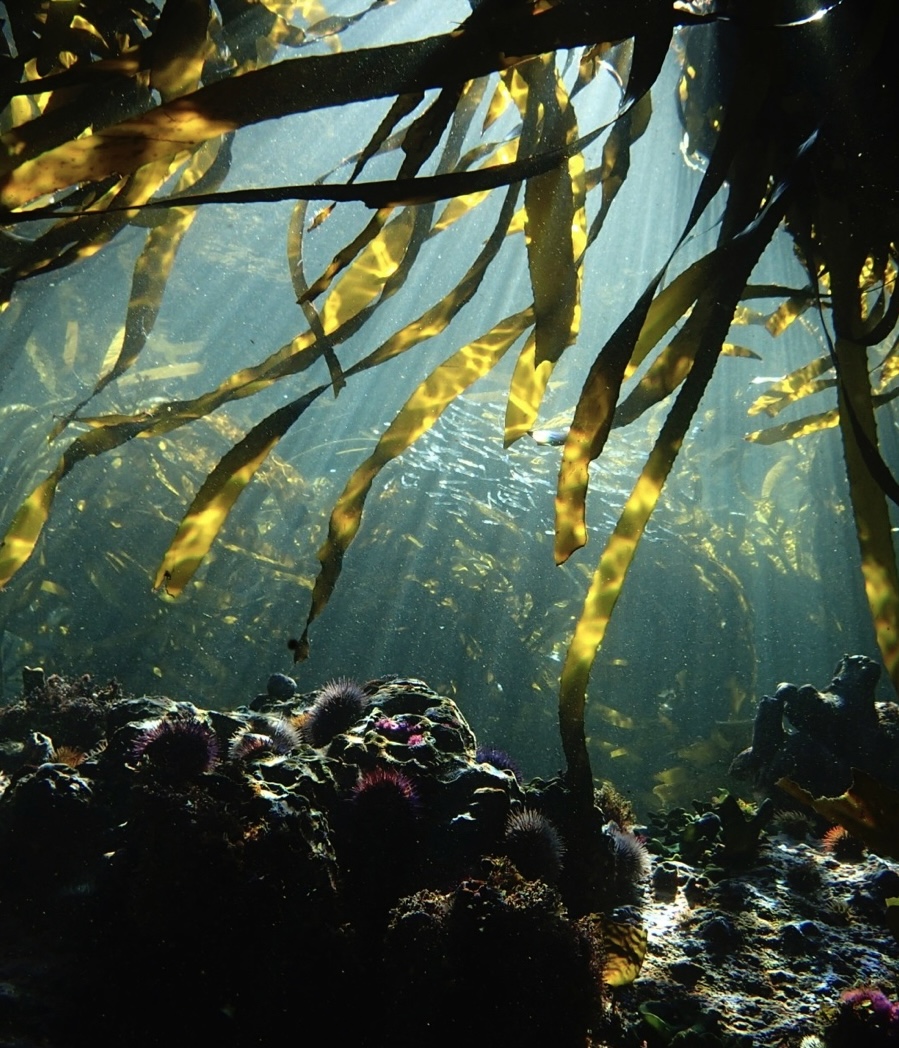

The Réunion Seahorse can be found as shallow as five metres and as deep as 60. It prefers sandy or seagrass areas and is not found on coral reefs. Meulepas and her buddy found this one while they were muck diving in a so-called shallow wasteland, away from a coral reef; There’s nothing quite like moving through the canopy of the Great African Sea Forest, and becoming part of it.

A very lonely Mauritian anemonefish gazes across a barren stretch of what used to be a thriving, colourful coral reef.

The Coastal Waters of the Black River District Hope Spot is home to spinner and bottlenose dolphins, a resident pod of sperm whales and other cetaceans. Humpback whales come here to nurse their young. The couple has spotted green turtles and hawkbills, pink whiprays, all kinds of scorpionfish, false stonefish, frogfish, ghost pipefish, moray eels and Mauritian anemonefish (endemic to the Mascarene Islands). They also believe they are the only ones to have footage of the rarely seen slow dragonet, endemic to Mauritius, in its natural habitat.

‘As an individual, you can feel powerless [to do anything about this]. But then I learnt about Mission Blue and I nominated the Coastal Waters of Black River District as a Hope Spot to connect with scientists and people passionate about protecting the oceans, share information and success stories, and reach out to local NGOs who already do a wonderful job and work hard to protect the oceans,’ says Meulepas.

Veranda Tamarin, under Rogers Hospitality, is one of the hotels in the area that takes sustainability seriously, educating staff, guests and the local community about protecting marine life and ecosystems and getting them involved in clean-up programmes in the village, along the beach and by the river. ‘Our engagement in marine conservation and protection includes a notable programme called the Coral Squad, developed by National Geographic, which aims to help educate local children about marine ecosystems, instil in them an explorer mindset and foster a sense of responsibility and care for the ocean,’ says Pooja Etwah, sustainable development executive for Rogers Hospitality.

Meulepas continues to rally support for the cause and find small ways to make a difference. She launched the Vetiver Project with local teacher Danielle Zélin and National Geographic Young Explorer Prashant Mohesh at Jardin d’Eveil in Albion, Black River. Vetiver is a ‘miracle grass’ that can purify water and control soil erosion with its metres-long roots. The idea is to plant vetiver around rivers, waterways, golf courses, cane fields and along the coastline to purify runoff water before it reaches the sea to give the coral reefs a fighting chance. This, together with expanding the mangroves (natural filters that maintain water quality and clarity as well as controlling nutrient distribution to seagrass beds and coral reefs), is an essential part of the solution to protect Mauritius from climate change.

‘It’s my way of giving back, for I am blessed to live on such a beautiful island,’ says Meulepas.

Meanwhile, in Cape Town, Mike Barron, a marine biologist, scientist and conservationist, PADI master scuba diving instructor and founder of Cape RADD (Research and Diver Development),

champions the False Bay Hope Spot. Home to more than 3 500 endemic marine species, including the star of Craig Foster’s award-winning documentary My Octopus Teacher, it forms part of the Great African Sea Forest, the only forest of giant bamboo kelp on our planet.

Fringing Cape Town shores and stretching north for more than 1 000km into Namibia, these are the ‘coral reefs’ of cold and temperate waters, as vulnerable to climate change and pollution as their tropical counterparts and as vital in their role as a carbon sink.

They sequester as much carbon as mangroves, salt marshes and seagrass meadows combined, reducing local ocean acidification, creating a refuge for marine life, protecting our coastline from storm surges and rising seas, and mitigating coastal erosion.

Incredibly, the Great African Sea Forest is growing, compared to elsewhere in the world where global warming is causing an annual global kelp forest loss of two percent. Its protection is vital.

Barron says there’s nothing quite like diving in the Great African Sea Forest. ‘You’re inside this three-dimensional ecosystem, not just floating over it but moving through the canopy. You become a part of it.’

The forest provides a home for a remarkable assortment of creatures, mainly invertebrates. The forest canopy attracts numerous schools of reef fish while a diverse range of sharks and rays depend on the sea forest for sustenance and shelter. Pyjama sharks can be found peacefully resting in small caves, often piled on one another, while gully sharks are abundant, gathering in groups of up to 70 individuals for mating purposes. Larger species like the bronze whaler, sevengill cow shark, smooth-hounds and even great whites gracefully glide past the scene. The short-tailed stingrays here reach lengths exceeding four metres.

The benefit of Cape RADD’s association with Mission Blue is communicating their efforts in monitoring biodiversity, which leads to funding opportunities that help them train the next generation of scientists and grow a community of conservation-minded ambassadors.

They work with thousands of people each year, teaching them about ocean conservation, shark conservation and the kelp forests – packaging recreational scuba diving and snorkelling excursions with a research component that might involve collecting data on shark populations or kelp diversity. This is the ‘eco-tourism citizen science side’ of the business where Barron and his team make it easy for everyone to access and engage with this environment. ‘It can be pretty overwhelming going into the kelp forest for the first time and not really knowing what you’re looking at. As specialists in the marine world, we can communicate what is going on and show them things they might otherwise have missed. They leave with a much better understanding and respect for the ocean and get a lot out of the fact that they contribute directly.’

The False Bay Hope Spot is one of six established along the coast of South Africa by Mission Blue in 2014, in partnership with the Sustainable Seas Trust. The others are Cape Whale Coast (from Rooi Els to Quoin Point, including offshore islands); Knysna (including the Knysna Estuary, marine coast and offshore waters), Plett (linking the Robberg Marine Protected Area to the Tsitsikamma Marine Protected Area), Algoa Bay and the islands (a sanctuary area hosting the principal breeding colonies of the African penguin) and Aliwal Shoal in KwaZulu-Natal.

Greet Meulepas’s greatest wish is for her daughter to be able to dive over pristine reefs and swim with dolphins and turtles. Hope Spots will ensure that when she is old enough to dive, the reefs and their inhabitants will be there in an immaculate blue paradise for all to share.